The Court Sets Forth Specific Guidelines to Avoid Compromising Ethical Considerations.

On June 27, 2010, we posted about the fact that Louisiana and Wisconsin are two states that do not allow the attorney general to hire a private attorney for a contingency fee. This limitation is proving to be especially significant in Louisiana, in the wake of the BP oil spill disaster.

Under People ex rel. Clancy v. Superior Court, 39 Cal.3d 740 (1985) (Clancy), public entities in California were barred from compensating their private counsel by means of a contingent fee agreement in public nuisance cases. Attorney James Clancy, who crusaded against the dissemination of pornography, relying on a public nuisance theory, had been hired by the City of Corona to bring nuisance abatement actions against a bookstore that sold “adult materials.” The California Supreme Court held in Clancy that public-nuisance abatement actions belong to the class of civil cases in which counsel representing the government must be absolutely neutral. However, Clancy’s hourly rate would double in the event Corona succeeded in the litigation against the bookstore; therefore, he had an interest extraneous to his official function in the actions he prosecuted on behalf of Corona. As a result, Clancy was disqualified from representing Corona in the abatement action.

Now the Supreme Court has revisited the issue of whether all contingent fee agreements between public entities and private counsel in any public nuisance action prosecuted on behalf of the public are prohibited. County of Santa Clara v. Superior Court of Santa Clara County, S163681 (Sup. Ct. July 26, 2010). The Court has limited Clancy in recognition of the wide array of public nuisance actions and the different means by which prosecutorial duties may be delegated to private attorneys without compromising ethical considerations.

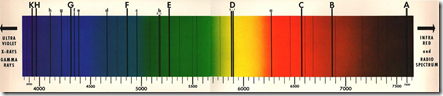

The facts of County of Santa Clara differ significantly from those in Clancy. In County of Santa Clara, California counties and cities prosecuted a public nuisance action against businesses that manufactured lead paint. The Court observed that, “[t]he broad spectrum of public-nuisance law may implicate both civil and criminal liability.” (And so the spectrum test was born . . . .).

The Court placed Clancy in this “spectrum” closer to a criminal action, whereas it placed County of Santa Clara closer to a civil action. The bookstore and its owners faced an injunction against future activities; in County of Santa Clara, the lead problems were in the past, the wrongful activity had ceased, and criminal statutes of limitation had expired. Also, free speech issues had been implicated in Clancy – in fact, Corona’s first attempts to shut down the bookstore were ruled unconstitutional – only then did Corona hire a private attorney with a personal interest in filing a nuisance action pursuant to a newly enacted ordinance intended to target the specific business:

“The history of Corona’s efforts to shut down the bookstore,” explained the Court, “revealed a profound imbalance between the institutional power and resources of the government and the limited means and influence of the defendants – whose vital property rights were threatened. . . . It is evident that the nature of the particular nuisance action involved in Clancy was an important factor in leading us to conclude the rules governing the disqualification of criminal prosecutors properly should be invoked to disqualify James Clancy.”

“Thus, because – in contrast to the situation in Clancy – neither a liberty interest nor the right of an existing business to continued operation is threatened by the present prosecution, this case is closer on the spectrum to an ordinary civil case than it is to a criminal prosecution.”

The Court has provided helpful guidelines for contingent fee agreements between public entities and private counsel, adopting, with slight modification, specific guidelines set forth by the Rhode Island Supreme Court: “(1) that the public-entity attorneys will retain complete control over the course and conduct of the case; (2) that government attorneys retain a veto power over any decisions made by outside counsel; and (3) that a government attorney with supervisory authority must be personally involved in overseeing the litigation.”

In County of Santa Clara, the contingent fee agreements did not satisfy all the guidelines just set forth: “Assuming the public entities contemplate pursuing this litigation assisted by private counsel on a contingent-fee basis, we conclude they may do so after revising the respective retention agreements to conform with the requir

ements set forth in this opinion.”Justices Kennard, Chin, and Moreno concurred in the opinion authored by Chief Justice George.

In a concurring opinion joined by Justice Rivera sitting by assignment, Justice Werdegar raised two interesting points.

First, she pointed out the possibility of conflict where the public attorneys have an incentive to advocate a cash settlement that is less “valuable” than injunctive relief to the public, as it would mean that the private attorneys could be paid without appropriation of public money – and the private attorneys too would have an incentive to advocate a cash settlement from which a contingency could be paid. But she deemed that the parties’ “briefing on the subject of possible remedies is so vague, any such conflict is merely speculative.

Second, Justice Werdegar was troubled that the efforts of defendants to disqualify private attorneys from being paid might be a late-in-the-game “tactical device”, and that the practical effect, if successful, would be to “preclude private counsel’s participation – in effect disqualifying them – . . . ” after a decade of litigation.

Blog Underview: In law school, co-contributor Marc clerked for Stanley Fleishman, an attorney who was a pioneer in two fields of law – First Amendment law, and the rights of the disabled. In the first phase of his career, as a First Amendment advocate, Stanley defended purported pornographers – and sometimes found James Clancy on the other side of the case. See, e.g., Jenkins v. Georgia, 418 U.S. 153 (1974) (holding that the film “Carnal Knowledge” was not obscene under constitutional standards), in which James Clancy filed an amicus brief for Charles H. Keating urging affirmance of the Georgia court, and Stanley Fleishman and Sam Rosenwein filed an amicus brief on behalf of the Adult Film Association of America, Inc.